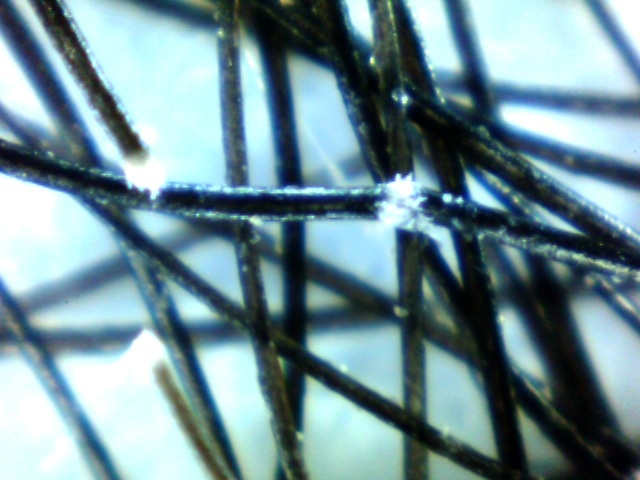

Possibly the most frequent cause of hair shaft severance. Swellings (nodes) develop along the hair shaft’s axis – seen as highlighted spots on the micrograph below.

Node disintegration (immediate / eventual) reveals the brush like macro fibrils of the cortex (trichoclasis). Severance is inevitable.

micrograph x 50 © B J Stevens

Causation:

Possible genetic inspiration (autosomal dominant trait).

A number of syndromic forms have been described.

Trauma:

Oxidative chemistry which reduces cystine levels.

Sea bathing and sunlight (Papa et al. 1972).

Hair straightening chemistry (Jolly & Carpenter 1967).

High temperature thermal styling.

From: Dr Pedro Madureira MD LTTS

Introduction

The essential abnormality of trichorrhexis nodosa is the formation of nodes along the hair shaft through which breakage readily occurs. In 1852, Samuel Wilks of Guy’s Hospital first described the condition, although the term trichorrhexis nodosa was not proposed until 1876 by M. Kaposi. Trichorrhexis nodosa is ultimately a response to physical or chemical trauma. Trichorrhexis nodosa may be acquired in patients with normal hair through exposure to a sufficient level of trauma. Trichorrhexis nodosa may also be congenital, occurring in defective, abnormally fragile hair following trivial injury. It is the most common congenital defect of the hair shaft.

It may affect the hair of the scalp, pubic area, beard, and moustache and may be particularly noticeable in persons of Afro-Caribbean descent because of hairstyling techniques. Hair care practices and hairstyles often used among women of African descent may contribute to trichorrhexis nodosa and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. The more common acquired form results from excessive or repeated trauma caused by frequent application of hair-permanent liquid, hair dyes, frequent brushing, scalp massage, and lengthy and repeated ultraviolet exposure, a reflection of the amount of trauma inflicted on the hair shafts rather than by some inherent or structural defect.

Figure 1 Trichorrhexis nodosa

Aetiology

The literature of the past century has repeatedly revived the controversy as to whether trichorrhexis nodosa is a developmental defect, sometimes hereditary, the consequence of acquired nutritional or metabolic disturbance, or solely a response to trauma, physical or chemical. Nor has there been any agreement concerning the incidence of trichorrhexis; some authors have considered it to be common, others rare. It is in fact the commonest defect of the hair shaft.

Trichorrhexis is best regarded as a distinctive response of the hair shaft to injury. If the degree or frequency of the injury be sufficient it can be induced in normal hair. The cuticular cells become disrupted allowing the cortical cells to splay out to form nodes. If, however, the hair is abnormally fragile trichorrhexis may follow relatively trivial injury. The trauma of hairdressing procedures has often been incriminated. Scratching may produce identical changes in the hairs in the genitocrural region.

Seasonal recurrence of trichorrhexis nodosa has been reported as the result of the cumulative effect of diverse insults to the hair. The manifestations appear each summer when repeated soaking in salt water and exposure to ultraviolet light were superimposed on the traumas of shampooing and hair brushing. Trichorrhexis nodosa has also resulted from the use of chemical hair straighteners and selenium shampoo and from trauma induced by infestation with trichomycosis axillaris. Numerous studies have reproduced trichorrhexis nodosa in both normal and affected hairs by exposing them to simulated physical and chemical trauma.

The severity of experimentally induced trichorrhexis nodosa was related to the degree of trauma, in patients with or without pre-existing trichorrhexis.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can occur due to nutritional deficiencies. Nutritional deficiencies, such as deficiencies in protein, biotin, zinc, and iron, can lead to weakened hair shafts and increased hair breakage. These nutrients are essential for the proper growth and maintenance of hair, and a deficiency in any of these can result in hair that is brittle, dry, and prone to breakage. Thyroid disorders and iron deficiency anemia can affect the health of the hair by altering the production of hormones that regulate hair growth and lead to weakened hair shafts and increased hair breakage.

Some authors have differentiated a generalized form from a much rarer localized form, often beginning early in life and sometimes genetically determined. Congenital and hereditary defects of the hair shaft can predispose to trichorrhexis nodosa is well established.

Some children have other characterized defects of hair shaft structure, trichorrhexis nodosa may occur in pseudomonilethrix, in Netherton’s syndrome or with pili annulate.

Trichorrhexis nodosa is a feature of the rare metabolic defect argininosuccinic aciduria, in which it is associated with mental retardation. Argininosuccinic aciduria is the autosomal recessive deficiency of argininosuccinase, the enzyme that cleaves argininosuccinic acid into arginine and fumaric acid in the urea cycle. It is comparatively rare in East Asian populations as compared with whites. Hair normally contains 10.5% arginine by weight. The deficiency in arginine resulting from this disorder produces weak hair with a tendency to fracture. The rare inborn deficiency of argininosuccinic acid synthetase results in low arginine levels and brittle hair.

Trichorrhexis nodosa may occur in certain families as an apparently isolated defect of the hair. Node formation and fracture are induced by minimal trauma and develop during the early months of life. Such a defect associated with abnormalities of teeth and nails was determined by an autosomal dominant gene.

In a case of generalized trichorrhexis nodosa in male adult electron histochemical study showed evidence of a disorder in the formation of a-keratin chains within the globular matrix of the hair cortex with respect to cystine. This cortical change together with vacuoles found in the endocuticle appear to be the defects which allow the formation of trichorrhexis nodosa in response to relatively trivial trauma.

The cutaneous photosensitivity that is sometimes evident may be the result of defective nucleotide excision repair. Three genes, XPB, XPD, and TTDA, have been linked as causative genes for this photosensitivity.

Epidemiology

Trichorrhexis nodosa is a rare disorder. A retrospective review of 129 hair-mount samples from 119 patients over a 10-year span found 25 cases of loose anagen hair syndrome, 6 cases of uncombable hair syndrome, and trichorrhexis nodosa in 13 patients.

Acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa is common in Blacks and appears to occur in individuals who are genetically predisposed. Some consider it an ethnic hair disorder. Acquired distal trichorrhexis nodosa primarily occurs in Asian or White persons. Acquired proximal trichorrhexis nodosa is more common in females than in males.

Congenital trichorrhexis nodosa may be present at birth, or it may appear within the first couple months of life. It can present in patients with the late form of argininosuccinic aciduria at age 2 years or older.

Clinical features

In trichorrhexis nodosa complicating a congenital defect of the hair shafts the hair breaks so easily that large or small portions of the scalp show only broken stumps and alopecia may be quite gross.

Figure 2 Trichorrhexis nodosa

In the much commoner conditions in which trauma plays a proportionately larger role and the predisposing inadequacy of the shaft a proportionately smaller one, there are three principal clinical presentations.

Proximal trichorrhexis nodosa occurs in Blacks. The hair is short in areas subjected to the greatest trauma, and trichorrhexis, trichoptilosis and trichoclasis are seen on microscopy.

Distal trichorrhexis nodosa occurs in other races. Often it is discovered incidentally and only a few whitish nodules are seen near the ends of scattered hairs. If many hairs are affected the patient may complain that the hair is dry, dull or brittle. On examination hairs with white nodules are seen among others which have fractured through the nodes.

The third clinical form was well described but it appears now to be rare. In a localized area of scalp, moustache or beard, some hairs are broken, and others show from one to five or six nodules. It is said that trauma of any sort can be excluded, and that spontaneous recovery eventually occurs.

Diagnosis

In simple trichorrhexis nodosa the shaft may appear normal with the light or electronmicroscope except at the nodes; or the shaft, apart from the proximal 1 cm, may show signs of abnormal wear and tear. At the nodes the cortex bulges and is split by longitudinal fissures. If fracture occurs transversely through a node, trichoclasis, the end of the hair resembles a small paint brush. More precisely, it is called a “paint brush fracture.” In patients with underlying trichothiodystrophy, polarized light shows the typical appearance of alternating light and dark bands on the shaft, the so-called tiger-tail pattern.

Figure 3 Microscopy suggestive of trichorrhexis nodosa

Figure 4 Trichoscopy

Fungal microscopy and culture may be performed if necessary. Patients suspected of having an underlying congenital disorder because of a young age at onset and because of the presence of associated symptoms warrant further investigation.

Analysis of the hair shaft may reveal a chemical deficiency caused by a metabolic disorder (low sulfur level in trichothiodystrophy). Serum and urine amino acid levels should be investigated.

Other blood tests may include copper level tests, iron studies, blood cell counts, and liver and thyroid function tests.

Treatment

The treatment of trichorrhexis nodosa involves managing the underlying cause, maintaining healthy hair care practices, and using targeted hair products. The avoidance of all the unnecessary trauma may be followed by marked improvement.

Trichorrhexis nodosa can be caused by various factors, such as nutritional deficiencies, thyroid disorders, iron deficiency anemia, and genetic conditions. Identifying and treating the underlying cause can help in the management of trichorrhexis nodosa.

To prevent further damage to the hair, it is essential to avoid harsh hair treatments, such as chemical relaxers, hot combs, and hair dyes. It is also important to avoid excessive heat styling, such as blow-drying and flat ironing, as these can cause further damage to the hair. Trimming the hair regularly can help remove split ends and prevent further damage to the hair.

Idiopathic trichoclasia

Idiopathic trichoclasia is a hair condition that causes damage and breakage of the hair shaft. It is a type of acquired hair shaft disorder, which means it is not present at birth and develops over time. Idiopathic trichoclasia is also known as brittle hair syndrome.

Trichoclasia is essentially a later stage of trichorrhexis nodosa, where the transverse fracture of the shaft of the hair is occurring at the middle of the nodes, as the hair loses its resistance to traction. It is a rare condition presenting as oval patches of varying size at the vertex or anterior parietals which on close examination reveal broken hairshafts with brush like distal ends reminescent of trichorrhexis nodosa but with a maximum length of 6 mm. The surrounding skin may be normal or lichenified.

The term “idiopathic” means that the cause of the condition is unknown. However, it is believed to be related to a combination of environmental factors, genetics, and hair care practices. Individuals with idiopathic trichoclasia often have hair that is dry, brittle, and prone to breakage.

Symptoms of idiopathic trichoclasia include split ends, hair that breaks off easily, and visible white spots or nodules along the hair shaft. These white spots are believed to be areas of air pockets or bubbles within the hair shaft, which weaken the hair and make it more susceptible to breakage.

The condition can be exacerbated by certain hair care practices, such as excessive heat styling, chemical treatments, and harsh brushing or combing. In some cases, underlying medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, malnutrition, or anemia can also contribute to the development of idiopathic trichoclasia.

Treatment for idiopathic trichoclasia typically involves avoiding or limiting hair care practices that can further damage the hair, such as heat styling or chemical treatments. Gentle hair care practices, such as using a wide-toothed comb, avoiding harsh hair products, and protecting the hair from the sun and other environmental stressors can also help improve hair health.

In some cases, dietary changes or supplements may be recommended to address underlying nutritional deficiencies that may be contributing to hair damage. Additionally, treating any underlying medical conditions can help improve hair health and reduce the risk of further damage.

Overall, idiopathic trichoclasia is a relatively common hair condition that can be managed with appropriate hair care practices and, in some cases, medical treatment.

Trichonodosis

The first description of knotting of the hair is said to have been given by Duncan Bulkley of New York in 1881. Galewsky (1906) coined the term trichonodosis, which is now generally employed.

The knotting of the hair shafts is induced by trauma. Short curly hair of relatively flat diameter is most readily affected. Knots were found most frequently in Afroid hair and in short, curly Caucasoid hair; none was seen in long, straight hair. In another investigation trichonodosis was found in 36 of 134 normal subjects: all those, male and female, with long kinky hair, over 50% of men with short kinky hair and 30% of males or females with long curly hair.

The only abnormalities are secondary to the knotting and are localized to that part of the shaft which forms the knot. In the scanning electron microscopy, the cuticle shows longitudinal fissuring and fractures, and cuticular scales are lost.

Trichonodosis is usually an incidental finding, for it is inconspicuous and must be deliberately sought. One or a few hairs only are affected. The trauma of brushing or combing may cause the shaft to break at the site of the knot.

Pubic and other body hair may show knotting, consequent to rubbing and scratching in the presence of pediculosis.

Figure 5 Trichonodosis

THE TRICHOLOGICAL SOCIETY